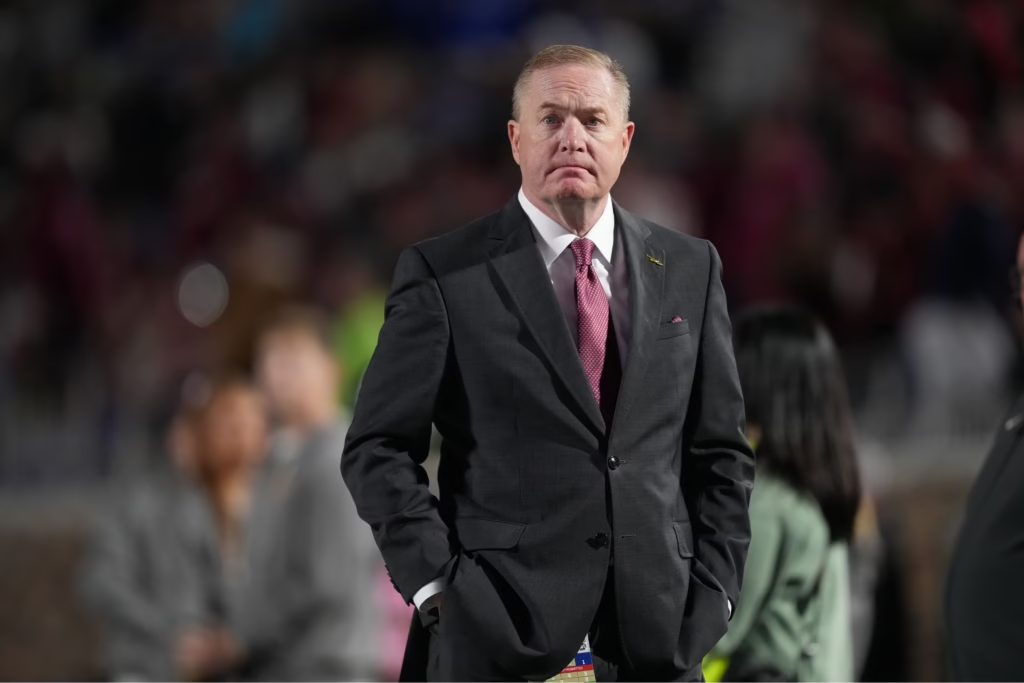

Michael Alford echoed a familiar refrain among college baseball’s power brokers after being named chairman of the Division I Baseball Committee last month: The sport has never been stronger, he told Baseball America.

The Florida State athletic director called college baseball “the best” and said his task now is to safeguard that rise and push it forward.

For Alford, that begins with conviction as much as policy. He describes himself as an “eye test” evaluator, a chairman who believes statistics and RPI formulas tell only part of the story. He expects committee members to watch games—not just box scores—and to understand teams well enough to see beyond their numbers.

It’s a philosophy rooted in both fandom and stewardship, as well as a belief that the committee’s work can shape the way the sport is consumed and celebrated. And as the game takes on greater visibility and resources in an era of sweeping change across college athletics, Alford sees opportunity in the chairmanship rather than burden.

“You know how much I love the game,” Alford said. “I just want to make it as good as we can make it.”

The NCAA Tournament has long been a showcase for the breadth of college baseball and a stage where powerhouses and plucky upstarts could collide on even terms. But that balance has largely eroded in recent years.

In 2025, 30 of the 35 at-large bids went to teams from just four conferences: the SEC, ACC, Big 12 and Big Ten. Oregon State, a conference independent, also secured a spot, leaving only four berths for mid-majors. It was smallest mid-major share since the NCAA adopted the 64-team super regional format in 1999 and a reflection of how sharply the sport has tilted toward its richest leagues.

That reality has sparked frustration across the sport, particularly among coaches who see the path narrowing for competitive programs outside the power structure.

Alford understands the sentiment, but his outlook is unapologetic. To him, the responsibility of the committee is not to preserve a sense of balance for balance’s sake but to ensure the postseason is stocked with the teams most capable of winning on the biggest stage.

“The best teams, the best talent should be in the tournament,” he said. “There’s no doubt about it.”

That conviction carries weight as the tournament itself undergoes a significant shift. Beginning in 2026, the committee will seed the top 32 teams in the field, doubling the number from years past.

Teams will be grouped into pods that directly correspond to regional matchups—the top four seeds will host from the 29–32 pod, seeds 5–8 from the 25–28 group, and so on. Three- and four-seed placement will not be altered under the current model, and conference restrictions will continue to take precedence over seeding in order to avoid league rematches.

The change is designed to create more equitable regional assignments and reduce the heavy hand of geography that has long influenced the bracket. For Alford, it is both a practical correction and a philosophical one that attempts to align the postseason more closely with performance.

“Some of these matchups are a little harder than others,” Alford said. “And they’re so geographically set that some are more difficult (and) unfair. And so this 1-32, I think, is going to help a lot to balance some regionals.”

Alford’s vision for selection leans heavily on watching games and developing a deep understanding of teams.

Numbers such as RPI and strength of schedule remain critical, he said, but only as supplements to the knowledge gained by actually following how teams play over the course of a season.

“I had the West Coast,” Alford said of his committee assignment last spring. “I knew everything about Santa Barbara. I watched it. I knew everything about (San Diego). You have to watch those games.”

That approach, Alford argued, allows committee members to appreciate context that raw data cannot always capture. He pointed to Hawaii, which impressed him early in the season before fading, and UC Santa Barbara, whose bullpen two years ago was formidable enough to sway his perception of the team’s postseason potential.

“At the beginning of the year (in 2025),” Alford said, “I was watching (Hawaii) going, ‘This is a damn good team that’s going to be in the tournament. I’m going to fight for them to be in the tournament, because they deserve it.’ But then, as the year went on, they kind of fell off a little bit.

“The point is, if you aren’t watching the games, the RPI or strength of schedule might not lead you to Hawaii. Watching the games will.”

For Alford, those case studies reinforce the importance of seeing beyond the box score.

“You can’t just come into the room and look at someone’s RPI and schedule,” he said. “You have to evaluate teams, and the eye test on teams matters to me.”

While that commitment might not restore the tournament to the days when mid-majors claimed double-digit bids, it could potentially give them a fairer shot. By pressing committee members to watch games across their assigned regions—not just the ones televised on ESPN’s main networks—Alford believes teams outside the power conferences will be judged more on substance than brand.

The stakes were made clear in 2025, when UConn and Xavier were left out of the field despite ambitious scheduling and competitive rosters. Both were widely cited as the biggest omissions in a bracket otherwise praised for its balance. Their absences reignited debate about whether mid-majors can still break through without gaudy records.

Alford acknowledged the disappointment but defended the process.

“They had an intent to schedule,” he said. “They did everything they were supposed to do. But then they just didn’t win enough. Two great teams, but in the eyes of the committee, they just didn’t win enough to move forward.”

Alford’s responsibilities extend beyond the bracket.

As chair, he will also help oversee the sport’s newly expanded governance structure, which now includes non-voting members charged with advising on issues outside tournament selection. He called the added layer a significant responsibility, one he embraces as another chance to shape the sport’s direction.

“I just want to lead the committee to do things to grow the game,” he said. “College baseball is such a wonderful sport. They have great teams, they have great coaches. What can we do to make sure that we continue to push the narrative and educate the fan base in so many different ways?”

One area already under review is umpiring. The NCAA in early August appointed Jeff Gosney as National Coordinator of Umpires, and Alford said he plans to work with Gosney to incorporate data more deliberately into officiating.

The goal, he explained, is to turn the numbers into both an evaluation tool and a teaching mechanism—a step toward greater consistency and accountability.

“I’m going to be working closely with him on making sure we utilize data and evaluation that we haven’t done before,” Alford said. “What can we use? What can we do to make umpires better as a teaching tool? I think it’s awesome that we have this capability, so let’s utilize it to the max.”

Taken together, Alford’s responsibilities as Division I Baseball Committee chair are expansive. He will be asked to manage the details of tournament construction, usher in the new seeding system and help implement data-driven reforms for umpiring. He will also stand as one of the public voices for a sport that continues to climb in visibility and relevance.

It is a job with reach far beyond the committee room, one that blends logistics with vision. And while the mechanics may evolve, Alford says the mission is clear.

“I just love college baseball,” he said. “I think it’s the best sport and I hope that will be clear in how I operate in this role.”

Discover more from 6up.net

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.